Are you planning to commission a mid-term review or evaluation of an ongoing programme? Getting ready to write up the Terms of Reference? Here some tips for consideration.

Stand alone? Is your programme by itself a major contributor to the impact you want to achieve? In other words, is it a fairly closed system so that it can be meaningfully reviewed in isolation of the actions of others? If not, would a review of a collective action make more operational sense? What other programmatic interventions would have to be included? Example: The relief responses for the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, or for the earthquake/tsunami survivors in Sulawesi, Indonesia, are fragmented, with target populations receiving complementary services from different agencies. Strong sector-coordination with weak socio-geographic coordination doesn’t help create integrated approaches. In Sulawesi, two donor agencies jointly supported a mid-term review of the overall response, through the total of 21 agencies they funded. In Bangladesh, three mid-term evaluations commissioned separately by three leading agencies, were perceived as an indication of insufficient collaboration.

Everything or focus? Do you need all components of our programme reviewed, or is it more useful to zoom the evaluation in on certain aspects? What could these be: perhaps the most expensive ones; the technically more challenging ones; or e.g. those that relate to people-centered action (inclusion, participation, information, accountability, protection…); impacts of your individual or the collective action on local capacities; or impacts of the intervention on the social relations (gender and age, social cohesion…), all of which are harder to manage and harder to assess? What will bring greatest value for your, and maybe the collective, ongoing programming here? Example: One donor commissioned an evaluation of the accountability-to-affected populations approaches of all the agencies it funded for post-earthquake reconstruction work in Nepal.

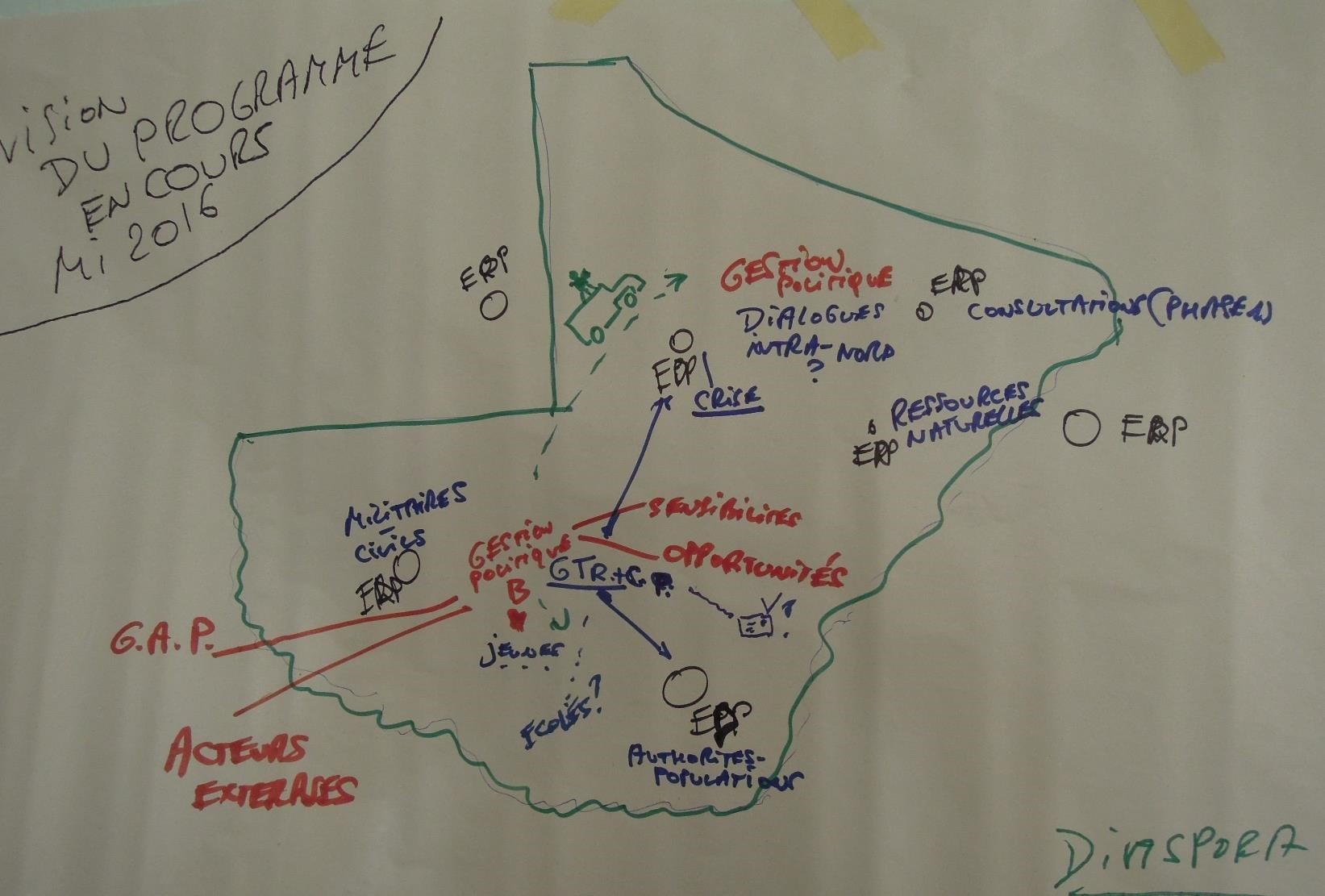

DAC criteria? How do you want to interpret the DAC criteria? Do you want to know whether you fulfilled the terms of our contract, or above else whether your programme is having meaningful impacts in this environment? The two may not fully coincide. Do you mostly want to hear reflections and recommendations about ‘what’ you achieved in your programme (task-focus) or, in a context with many other actors with complex power dynamics, also ‘how’ you are engaging with the many stakeholders (relationship focus)? Is the contextual relevance of your programme a question that can be fairly straightforwardly assessed, or does it require deeper contextual understanding and a critical reflection on theories-of-change? Example: An evaluation of a programme supporting local peace capacities in north Mali, revealed its disconnect from other, larger peace- and governance reform initiatives. That required the evaluators to take a broader look, at the bigger picture. How in practice can efficiency be meaningfully assessed? What data do you have, for example how, in your decisions, ‘cost’ was weighed against other considerations? Is it possible already to asses impacts and the question of sustainability, or is it still too early? Are there other sector-wide benchmarks or thematic references than DAC criteria that must or can be reviewed here? Have you, as an organisation, made public commitments to certain ways of working; do you want the mid-term exercise to assess how you are living up to those?[i] Could you ask the evaluators to look at whether earlier institutional (and sector-wide) learning is being drawn upon?

Must hear? Whose views and experiences on all this do the reviewers definitely need to hear? Who are important stakeholders whose voices and views are seldom heard? If these are e.g. our intended beneficiaries, clients, partners, local authorities – will you give the evaluators enough time to also listen to them - after they have met with your staff, donors, other agencies? Might you suggest they first listen to these actors, and only afterwards to you and your closest partners?

Relevant time span? Do you have a prior history of engagement in this environment? Is that relevant for the programme that you currently want reviewed? How far back in time should the reviewers ideally go? Do you also want a forward-looking perspective? Can you offer the reviewers/evaluators the additional time to familiarise themselves more deeply with the context and explore possible future scenarios and the key factors that will shape them? Example: One mid-term evaluation was framed to cover six months. As the evaluators decided not to do a data-collection stop during the process of successive draft writing, the final report covered eleven months. But as it took into account relevant prior history and, as requested, looked forward at possible scenarios, the overall time horizon became 7.5 years.

Data quality, sources and interpretation? Do you have good enough data on what you would like reviewed, that go beyond activities and outputs? If not, how much time will the evaluators need to collect such key data? Are the sources of your data relevant and diverse enough, to consider the data representative enough? Are you confident of the interpretation you made of your own and other available data? Do you want the reviewers to check this, and test alternative interpretations? Again, what would that take, practically? Have you already tried to capture also unintended effects and consequences of your programme, or do you want the reviewers to inquire also into this? What would that take, practically? Example: An evaluator was given the results and trend interpretation of three consecutive surveys. A closer look however revealed that some of the questions in the consecutive surveys had changed, and that -unintendedly- the survey respondents were not the same. While this didn’t fully invalidate the interpretation, it reduced its confidence-level.

Controversies? Are there controversies in your programming environment, e.g. about a policy decision, about coordination leadership, about what authority to relate to if there are contesting authorities? Do you want the reviewers to look into those, and give you advice on how to resolve them, or at least navigate them? Example: A mid-term evaluation of a programme supporting internally displaced people, could not ignore the new government policy pushing the displaced to return, when many places of origin were not sufficiently secure and had no basic services. Dilemma-management is often part of programme or larger strategic management. Why not have a review look into that?

Real-time? Who in your organisation will have the time and stamina to engage attentively with successive drafts of the report? If you want the insights and guidance of this review to serve you in real-time, how to avoid getting too delayed by waiting for a final report? Example: The process of successive drafting and commenting on drafts, of a mid-term evaluation of several strands of work in a complex situation, took a good two months. While several of the attention points mentioned in the first draft had been picked up by then, others got lost in the back-and-forth conversations. Put emphasis on the debrief & learning workshop(s) at the end of field work, not only on the final report. Alternatively, if you are operating in a very complex and/or changing situation, could you consider an iterative review process, with some repeat visits? That could maximise the value of the reviewers as they get to know the context and the interventions in it much better, but also gives them more of an accompaniment role.

Recommendations how? Do you want the reviewers to immediately tell you their recommendations? Or are the questions you ask them to explore actually your questions?[ii] Is it useful to outsource the thinking? Can you ask them to hold back their recommendations and at first only present their findings, so you have an opportunity to consider where these findings tell you you should go?

In the public domain? Will you put the report in the public domain? Will that generate defensiveness? Can you project yourself as an organisation that welcomes positive but also critical feedback, because it is in line with your culture of continuous improvement?

Evaluability? Many options, to make the review or evaluation exercise a very interesting one. But reviewers/evaluators can’t do miracles. Check the evaluability of your programme – and how much review/evaluation time you can get with your budget. Did you state clear objectives for what you intended to achieve with your action? If not, it will not be possible to evaluate whether you achieved what you set out to do. Do you have baseline information, if not very detailed and quantified, at least a good enough description of the situation as it was when you started out? If not, it will be harder to assess what has changed because of your intervention. Are all stakeholders that the reviewers must speak with accessible, who is not and what does that mean for the evaluation? Example: The Terms of Reference wanted an evaluation to cover a programme extending over several areas in Southcentral Somalia. But, for security reasons, the evaluator could not leave a well-protected compound in Mogadisho. This cannot be compensated for with a few phone calls to people outside Mogadisho.

Above all, are your means proportionate to your expectations: do you have the budget to give the evaluators the time they practically need, to meet all your expectations? Example: One Terms of Reference asked for an evaluation of a three-year programme of engagement with 10 very different institutions, plus a forward-looking perspective. The budget however only allowed for 5 days in-country: not realistic! You can’t buy a Rolls Royce with the budget of a Fiat. However, consider joining up with another agency to co-fund the exercise. Otherwise, what choices must you make to bring your ambitions in line with your means? Can a methodologically lighter ‘review’ still give the guidance you need?

[i] See “Humanitarian Evaluation: Include Grand Bargain references”.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/humanitarian-evaluation-include-grand-bargain-koenraad-van-brabant/

[ii] See “These Questions are Ours: Evaluative thinking beyond monitoring and evaluation”.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/questions-ours-evaluative-thinking-beyond-m-e-koenraad-van-brabant/