I. Organisational Capacity is More than the Sum of Thematic-Technical Expertise.

A few months ago I was in conversation with a non-Western organisation, who had advertised for ‘OD support’. In 15 days they wanted one consultant to do what sounded like ‘everything’, including reviewing the functioning of the governance organs, developing stronger external communications and fundraising strategies and drafting a finance manual. My suggestion that ‘internal communications’ might be important didn’t seem to resonate. Apparently we had different understandings of ‘organisational development’, how it differs or not from ‘capacity-development’ (CD) and what an appropriate role is for an OD adviser. This is generally the case, so let me offer here a glimpse of different lenses on and approaches to OD.

First a few clarifications:

By ‘capacities’ I mean the ability of a formally or informally organised group of people to perform certain tasks with a decent level of thematic, technical and/or procedural skill. If we want to improve these ‘capacities’, we can call on specific expertise such as a finance, communications, gender or public health specialist. Developing such capacities in-house certainly adds some ‘organisational’ strength. But it does not necessarily add up to better overall organisational performance. This can, and often is, affected by internal disconnects of a different nature.

Every ‘organisation’ is more than the sum of its parts, and has a certain existence and life of its own. ‘Organisational development’ happens at that systemic level. An OD adviser looks at the dynamics of different interrelated elements within a holistic perspective.

The nuance can be observed, for example, with regard to ‘mainstreaming’. Many ‘mainstreaming’ efforts struggle because they are pursued with a technical/thematic rather than an OD perspective.

II. Capacity and Organisational Assessments: Why and Who?

Who initiates the ‘capacity’ or ‘organisational’ assessment and why, are two factors with significant influence.

In the international cooperation sector, such assessments often precede a decision whether to fund or to partner with another organisation. (Reciprocal ‘assessments’ are extremely rare.) We all tend to become defensive when something feels ‘imposed’ from outside: internally initiated and ‘owned’ CD or OD exercises are likely to have more traction. But internal ‘assessments’ are often initiated because of a perception that things are ‘not working so well’. If only the senior management’s view of ‘what is not going well’ is heard, resistance from the other people is likely.

Both triggers share an underlying concern for a potential risk, or the perception there is a ‘problem’. Why not undertake such assessment out of a more positive, developmental sense, to stimulate the potential to go to the next level?

There is a multitude of frameworks and approaches. Their choice is not neutral or simply a matter of ‘technical superiority’ of one over the other. Choices can be tactical, but also have a much deeper influence on where the exercise leads, as the following examples illustrate.

III. Pyramidal Organisations. Assessing Form and Functioning.

a. Are you properly dressed?

Here the assessment concentrates on whether the organisation under review has the markers that you would expect. We look at its structures, policies and procedures: Is it legally registered, does it have a governing entity that provides oversight, does it have a mission and vision statement, human resource and financial policies and detailed procedures that meet minimal standards? Do people have job descriptions, are there salary scales, independent audits of accounts, no conflicts of interest at management or Board level etc.

In essence, we examine whether the ‘form’ corresponds to what we expect from a ‘modern’ organisation, particularly if it handles public money. For those familiar with Matt Andrew’s work on institutional reform in development: has the organisation successfully ‘mimicked’ i.e. imitated, the external model? Relevant as it may be, this approach on its own largely misses the ball: organisations are like ice-bergs, most of it is hidden below the surface.

b. Within those clothes, how healthy are you?

Nice clothes may hide a diseased or feeble body. McKinsey research has established a strong correlation between sustained organisational health and superior performance. One excellent framework to assess what shape different parts of the body are in, is the BOND ‘Health Check’.

The ‘Health Check’ focuses on 11 ‘pillars’ that relate to core functions: Identity and integrity; Leadership and strategy; Partners; Beneficiaries; Programmes; People; Money; External Relations; Monitoring (not a good head title); Internal relations; and Influencing. For each pillar there are several components or indicators. For each component, the participants in the exercise can choose between statements that indicate a progressive improvement, and explain their choice. For example: ‘Communications’ is part of the ‘External Relations’ function, and respondents can choose between statements that describe a spectrum, with as lowest score “We use a few methods to communicate our work. Communications are ad hoc and there is no formal planning” and as highest score “We have a communications strategy that defines our target audience and key messages and channels. (…) We are coherent in how we communicate in our fundraising, public education, and advocacy work.”

Such self-assessment can be done by senior management alone. It can better include all staff, and even other stakeholders, such as volunteers, supporters, suppliers, partners, beneficiaries etc., along the lines of a ‘social audit’.

This ‘Health Check’ is not overly focused on the ‘form’, but understandably contains references that suggest certain hierarchies (from CEO to intern), structures (departments, country offices), processes (strategy, planning) and policies and procedures (finance, HR).

When checking on the clothing, we are likely to look for what is wrong or missing, that would mean that the organisation cannot now be invited to the party. The health check is more balanced. But our tendency for ‘deficit thinking’ i.e. to focus on the gaps, the weaknesses, what is problematic, may still creep in.

IV. Going Deeper: Images of organisation.

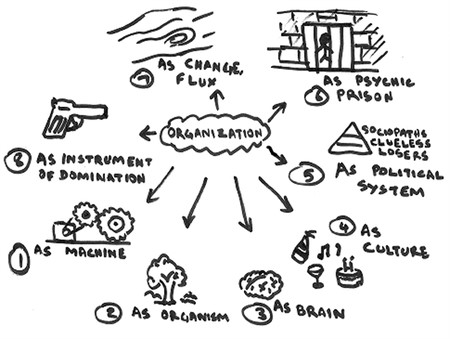

In 1986 Morgan published his ‘Images of Organisation’. He argues that organisations are built and experienced according to certain mental images. More often than not, these are unconscious. He identifies eight different, not necessarily exclusive, images, visualised here. Organisations can be imagined as ‘machines’ or as ‘organisms’, as something like the ‘brain’, or through the dominant lens of ‘culture’. They can be looked at as ‘political systems’, as ‘instruments of domination’ and experienced as ‘psychic prisons’. Or they can be understood as something in constant change.

Morgan’s mental images seem to cover a spectrum. On one end there is the organisation as an instrument of domination and therefore a political arena. This can easily result in employees being treated like cogs in a machine and ‘psychic prisons’: people at all levels become stuck in certain perspectives, mind-sets, patterns of interpretation, behaviours and processes, that make it near impossible to see other aspects of reality and to adapt or innovate. Towards the other end of the spectrum is the image of an organisation as an organism, a living entity, that understands its existence in a wider eco-system. This is much more self-organising, and more open to evolution and transformation.

The ‘brain’ image considers organisations as information processing and learning systems that, like the brain, can and have to be both ‘specialised’ and ‘holistic’. This perspective is relevant on any point of the spectrum, just as that of organisational ‘culture’, the intangible ways of ‘how we do things here’.

Morgan's ‘images’ bring to the fore important dimensions of organisational life and performance, that the previous approaches did not pick up very well. Certainly those of ‘power’ and ‘culture’ that can be anywhere on a spectrum between ‘stifling’ and ‘enabling’. At a deeper level perhaps the fundamental difference in an outlook (including of the OD adviser or management consultant) that sees organisations mostly in ‘machine’ terms, or more as a ‘living organism’.

In the first view, which dates back to the industrial revolution and Taylor’s 1912 ‘Principles of Scientific Management’, employees, but also clients or patients, risks becoming functional cogs in a machine, largely interchangeable numbers. While an organisation that is a living organism is made up of a complex network of interacting living cells, that provide it with its life force. (A second image or mind set can come here into play: when some cells become dysfunctional and threaten the wellbeing of the organism, they can be destroyed by a more or less targeted intervention, Western-medicine style. Or we can change our life style and boost the immune system, in a more traditional Eastern medical approach.) Moreover, a machine is fairly self-contained, an organism exists in a wider eco-system.

Too abstract, less practical than the ‘Health Check’ for example? In a certain way yes. But it is also possible to explore where an organisation is at now, and where it wants to go, using these images. Example questions: 1. You observe that many decisions seem to be influenced by personal ambitions (Political System). How can you move to decision-making more based on information and reasoning (Brain)? What may enable that, what resistance is likely to arise from whom? 2. You feel that you are all too stuck with certain perspectives on the ‘world out there’ (Psychic Prison), and that your way of operating is losing effectiveness in a changing world. How can you create a culture that encourages adaptation and even innovation (Organism/Change Flux)?

V. When a Glass Half Empty Becomes Half Full: Appreciative Inquiry.

‘Appreciative Inquiry’ was developed as a lightly structured change strategy. But it is also a mind-set. It is the opposite of deficit thinking. Rather than focusing on the gaps and what is not going well, it seeks to identify the strengths and to do more of what works well. Appreciative inquiry sees organisations as living organisms and believes in their adaptive and creative potential. To Morgan’s attention points about organisational life, it adds another factor: energy levels and the nature of that energy.

AI invites people to focus on the positive experiences, and bring out the ‘best of what is’. It then encourages people to consider the next positive level and to envisage what that looks and feels like. Along the lines of a GROW coaching approach, it seeks to catalyse the collective energy to bring that positive future about.

There is nothing naïve about the approach. Anybody with some working experience appreciates the impact of the broader ‘atmosphere’: Where there is constant focus on the negative, our energy, commitment, sense of responsibility and creativity goes down. When there is regular appreciation of the positive, our drive to do even better is stimulated.

Deficit thinking prevails in the international development sector and in many work environments. Here and there however, an ‘appreciative inquiry’ mind-set can be detected. For example, in the now fashionable celebration of ‘resilience’ instead of ‘fragility’, and in the advice to learn from ‘positive deviance’ cases: in the real success stories, identify the key enabling factors that we need to take with us or create elsewhere.

VI. Out-of-the Pyramid: People Working Together for a Purpose.

Most of us have never experienced other than pyramid-shaped organisational structures. We understand their rationales that underpin a functional division of labour to maximise specialist expertise, command and control to ensure compliance and performance, and a strategically structured drive for greater efficiency and growth in a competitive market.

Most of us have also experienced the drawbacks: Silos and turf wars; internal politicking for personal advancement; a 'work space' where everybody plays a public persona and leaves most of who they are at the door; narrowly walled ‘job descriptions’ that you cannot grow into or grow beyond; employees that get dismissed when their unit or function is less needed rather than be enabled to change role to another part of the organisation, general frustration with the obligatory annual performance reviews, and top managers who – only in the private space with their coach- admit to their exhaustion from all the politicking and sense of emptiness because they live inauthentic lives.

Yet there is a surprising number of not-for-profit and for-profit organisations, across a range of sectors from manufacturing and services, that operate very differently. Some comprise thousands of people. Some are even publicly listed.

The foundation of this is the collective responsibility and accountability for the overall performance, survival and development of the organisation. These ‘organisations’ shape as networks of teams instead of a pyramid. Teams make commitments among each other and with other teams and hold each other accountable on an ongoing basis, not once-a-year. The fundamental functioning of individuals is framed in terms of ‘roles’ rather than a ‘job’. People can shift roles, picking up something that needs to be done, or do so for a longer period if their colleagues believe they qualify for it. Leadership is distributed and not monopolised at the top. Decisions are not constantly pushed up and down through management systems that generate a lot of friction. No decision can be taken by anyone without a mandatory advisory process. Inevitable divergence of opinion is channelled into constructive rather than toxic ‘conflict’. All are trained in constructive conflict resolution. If need be external coaches can be called upon.

Self-managing organisations also face internal and market place challenges: But they tap into the collective commitment, creativity and positive energy, to deal with them.

This is not some sort of hippie idealism or post-communist collectivism. Twelve fairly ‘radical’ such cases are well described and analysed by Laloux in his ‘Reinventing Organisations’. (You don’t need to subscribe to his evolutionary perspective, to appreciate the case research). But there are many more trends and examples in the same direction. We’ve heard about Google company giving its employees 20% of their time to pursue their own projects (they didn’t invent this). They have made the choice to create innovation space for all, rather than set up an ‘innovation unit’. But Laszlo Bock’s (Google's top HR person) ‘Work Rules’ book (2015) reveals wider working practices that encourage collective responsibility and high degrees of self-management. Google still has ‘managers’, but their ability to abuse their power and make unilateral decisions is strongly controlled. Google has its own version of ‘kaizen’: continuous improvement, for which everyone in the company can bring up ideas. And because it chooses belief in people rather than distrust as starting point, it also practices great internal transparency. Good only for geeks? Bridgewater Associates, one of the world's major hedge funds, records every meeting and makes it available to all employees.

Not convinced? Are ‘hackathons’ and ‘crowd-thinking not approaches to tap into the collective talent?

Not possible for really serious matters? Well, in 2012 Swiss voters in a national referendum rejected a proposal to increase the annual paid holiday from 4 to 6 weeks. Because they felt it might affect their economic competitiveness. In the political community of Swiss Inc., citizens have much more influence than in most other Western-style ‘democracies’. Because they feel a strong sense of ‘ownership’ for their collective wellbeing, they handle their citizenship rights and duties generally with great responsibility. A nice example of people at all levels not choosing for their immediate self-interest (ego-system), but based on the wider consideration: how do we keep this habitat (eco-system) healthy and thriving?

Machines and organisms experience change very differently: Pyramids like to keep their shape. Change is very painful. The existing shape needs to be ‘unfrozen’, then a change process pushed through usually in the face of ‘resistance’, and the new shape then refrozen again. According to McKinsey research, less than a quarter of organisational redesign efforts succeed. By contrast, living organisms know that change is inevitable. There will be less intrinsic resistance to change.

Swift changes in the environment of course can be catastrophic for an organism. Just as machines go out-of-date or ‘kaput’. But consider the potential of all members of the organisation, rather than just a few managers at the top, scanning the internal environment for ways to improve and the external environment for developments that may affect it, for opportunities for new work, new sources of income, new ways to provide value to people.

How do you work with this as an OD adviser? You go back to the source: An organisation is a group of people that come together for a purpose. Collectively they are more than the sum of the individual parts in terms of energy, competency, creativity etc. So what social contract can they establish with each other, that creates an enabling atmosphere for all to bring the best of themselves (not just the ‘work persona’) in the service of that purpose? What does that mean then in terms of how work is shared, how decisions are made, how salaries and benefits are determined and distributed, how responsibility and accountability for the quality of work is handled. And what relationship it seeks with external stakeholders?

Many of us engaged in international cooperation want to encourage healthy social and political contracts between citizens and the state authorities. We advocate for inclusion, dignity, all voices to be heard. The World Bank and others promote the learning about approaches for greater ‘citizen engagement’. Several of us have gone on leadership courses where we learned about the superior potential of ‘transformational’ over ‘transactional leadership’.

Did Gandhi not advice: ‘Be the change you want to see in the world!’ Surely we are able to consider ‘social contract’ forms for our collective work, other than largely transactional hierarchies?

VII. A Middle Way: The 5C Framework.

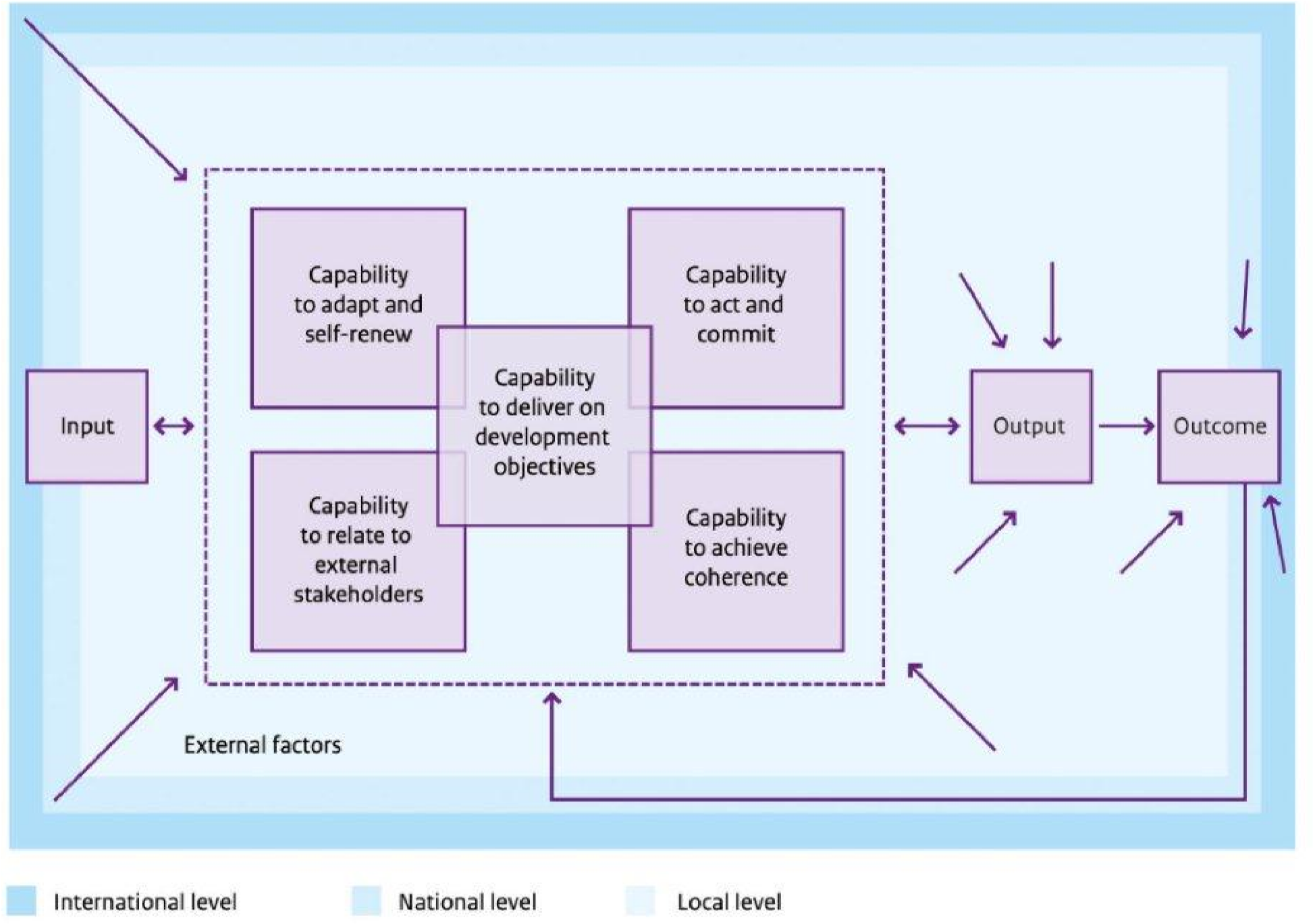

If we recognise that purpose and people are central to organisational life and evolution, but don’t want to do away too quickly with structure and procedures, the 5Cs framework can serve us well. It emerged out of a comparative study by the ECPDM of very divers organisations in different countries (Baser & Morgan 2008).

The research showed that sustainable organisations are fairly strong in 5 core capabilities. The capability to ‘deliver on objectives’ (or to create value for others) we understand easily. The capability ‘to commit and to act’ is not just a matter of material and financial resources. This also refers to the overall level of motivation, energy, confidence, will to move forward also in the face of constraints and setbacks. The ‘capability to relate and attract’ considers the multitude of relations with external stakeholders and those we seek to influence. But also to the ability to attract and retain financial support and good colleagues. The capability to ‘adapt and renew’ covers re-positioning and responding to changes in the external environment, but also pro-active innovation and renewal from within. The organisational ability to learn fits here too. Finally, the capability to ‘maintain internal coherence’ draws the attention to other challenges: does the organisation practice what it preaches, does geographical or functional dispersal lead to fragmentation or not, how can participation still lead to effective decision-making, what is a healthy balance between needed stability and equally needed change?

The 5Cs framework does not presume a certain form, pyramidal or other. As a flexible approach it creates space for conversations that can focus on the weaknesses and failures as well as on the strengths and successes. It can be done with different circles of participation. It is possible to zoom in on one ‘capability’ as a priority area. Without losing sight of the broader system.

VIII. So what now?

Do you need to make a choice between these, or any of the other frameworks and approaches available? No, most OD advisers draw on several. More importantly, choose what best fits the situation and the entry point that is given: Often there will be openness to something like the BOND Health Check, or the 5Cs framework for broad, canvas-wide conversations. Deeper inquiry into the internal dynamics of power, relationship, responsibility and accountability can feel threatening. That requires trust in the OD adviser. And a strong organisational focus on ‘purpose’ rather than ‘power’ and ‘position’. Use your relationship and asking skills to slowly move into these sensitive but vital aspects that really determine organisational strength.

1. Jeffrey Swartz as CEO of Timberland, quoted by Adam Bryant as ""it wasn't your résumé we hired, it was you." The Corner Office 2011: 216