The political economy of international cooperation: Be it Mali, South Sudan or another country with a large international foot print, you will find a bewildering multitude of actors all wanting to strengthen the national institutions, many of them operating with their own agendas and priorities.

The political economy of the national public sector. Similar disconnects may exists within the national public sector, preventing the effective pursuit of a coherent national strategy.

The hidden organisation: Organisations are like ice-bergs. Most of their real functioning lies below the surface and does not necessarily correspond to the formal structures, policies and processes.

Certainly those expert advisers with a more strategic than operational mandate, need to develop some understanding of the undercurrents in this landscape, and how to navigate those, if they want to have a chance of being effective.

III. WHAT YOU ARE GIVEN.

Expert advisers can find themselves with a given mandate, role and position. Ideally this has been thought through carefully, and agreed in genuine partnership with the national institution where s/he will be deployed. In practice, that is not always the case. The initial conditions may be constraining rather than enabling. Consider some factors for example:

- Who really wanted the adviser and why? The national entity, because they recognise a real need for external expertise and not because they must take the foreign adviser to access the aid money? Or the bilateral or multilateral ‘development partner’, who wants the national entity to reform in a certain direction and/or puts in an adviser also to keep an eye on the aid money?

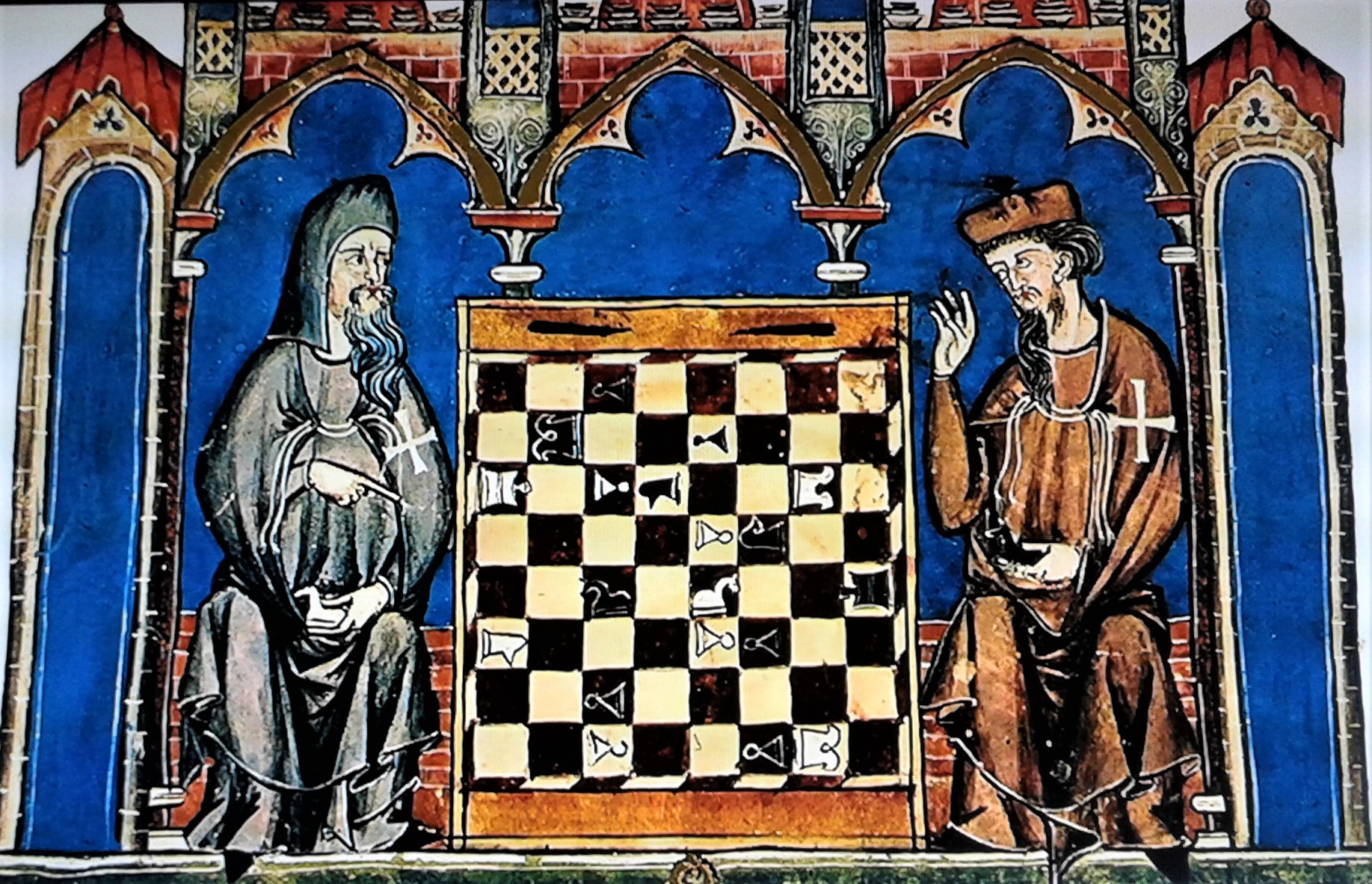

- Other advisers: Many advisers are not the only or first one in working with a national public sector institution. How will you relate to the other international expert advisers working with the same institution? In principle you work towards the same goal, but do you follow the same pathways, give similar or complementary advice? Do you have similar interpersonal styles? The same sense of urgency or patience? Or are advisers, like historical courtiers, competing for the ear of the principal national counterpart? And how do the foreign advisers relate to the national policy advisers, who may not come along with a purse in their brief case?

- ·Where do you sit? Do you sit in the office of an international mission (probably with a back-up generator and hence uninterrupted air conditioning, internet access and printing facilities)? Or in the office of your national counterparts? Being with them can help develop the relationship, mutual understanding and collaboration. But it may also increase the temptations for the ‘adviser’ to be more of a ‘do-er’.

- 8 x 1 is not the same as 1 x 8: The 2011 World Development Report observed that significant and lasting positive changes in governance take on average between 17-27 years. What time frame are you given? Many advisers are deployed on annual, renewable contracts, some even shorter than that. This may suit the budgetary cycles of the entity who pays them, and their own interest. But by the time they begin to get some understanding of the landscape in which they find themselves, and have developed good relationships with a broad set of key actors and stakeholders, their term is up. As Alwin van de Boogaard, who was an adviser in Burundi for eight years, points out: Eight consecutive annual plans (let alone 4 to 6 different consecutive advisers) is not the same as a general plan that from the outset works with an 8-year (i.e. medium-term) time horizon – and a continuity of adviser.

Advisers may be able to create a bit more room for manoeuvre here than when it comes to the overall political economy. But they will have to work on it consciously. And it requires other skills than the technical-thematic expertise for which they were selected.

IV. ELEMENTARY, DEAR WATSON.

This being the setting, it is clear that advisers need certain ‘political capabilities’. For ‘political advisers’ this is of course well recognised. But not for the ‘technical-thematic experts’. A variety of reasons probably explain this. One of them is the belief that the institutional fragility and underperformance of the public sector elsewhere, is essentially a problem of ‘knowledge’. So we can solve it by offering ‘knowledge experts’. Perhaps another reason that if we wanted ‘knowledge experts’ who are also decent ‘political animals’, we wouldn’t have that many to offer? Or they might not be so open to serve the political interests of their home country?

There are other necessary competencies, many of which go unrecognised or are undervalued:

Broad and reflected comparative experience. There are still ‘expert-advisers’ who know extremely well how a certain government institution works in their home country. But have no broad comparative perspective and are not necessarily familiar with the learning from comparative experience. One of the consequences can be divergent paradigms and contradictory advice. As a senior military from a Western country told me, who had been working as an adviser with the top command of the Afghan army: “The Americans were building an ‘American’ style Afghan army. The British a British-style one. Other countries advised along the lines of their national armies. Nobody was building an ‘Afghan’ army.” Different development partners sometimes supply different types of equipment to the same national counterpart institution. Who then find themselves with additional maintenance and repair problems. So too, different organisational (and political) paradigms will reduce the functionality of the national institution they want to strengthen.

A real ‘expert’ adviser has to be familiar with different approaches from different countries, say for the financing of health care, and can explain to the national counterparts what the underlying logics and consequences of each are. None of them has to be a model to be copied. National actors can use that diversity as a source of ideas to craft their own institution. You would also expect an ‘expert’ adviser to be well familiar with the critiques and learning from wider comparative experience, say for example on the reintegration of ex-combatants, so that known mistakes are not repeated. That is not necessarily the case.

Shift from ‘do-er’ to ‘adviser’. Some, not all, experts have been do-ers. They are acting members of their national police force or army. They normally work as e.g. auditors, prosecutors or departmental managers in their home country’s tax revenue office. We can excel as do-ers, but feel uncomfortable or ill prepared to act as mentors or facilitators. Relinquishing control and resisting the temptation to take over and do it yourself – because it will be done quicker and better- can be a difficult attitudinal change.

Strong interpersonal skills. Daniel Goleman has drawn our attention to ‘emotional intelligence’, and to ‘social intelligence’. In essence this means: self-awareness and self-management, awareness of the other and management of the relationships with others. Effectiveness in our work is not only a matter of rational intelligence and argument. It also dependents on how we relate to and work with people. In which the one element that we potentially have most control over, is ‘how’ we are. Being an effective adviser, just as being an effective leader or change agent, requires conscious investment also in personal development.

Cross-cultural competencies. When I started meeting my wife’s family in India, she impressed on me several behavioural do’s and don’ts. Always showing respect to elder was one. Another, never to point my foot soles at someone else: as they carry the dirt from outside, this is very insulting. Remember the Iraqi who threw his shoe at George Bush Jr? Losing your temper in Asia is generally seen as extremely bad and shameful behaviour. When the Japanese negotiate, they seek to establish a relationship and a win-win situation. They need to adapt to Western styles of negotiation that often aim at a win-lose outcome. Small things in the eyes of some, but not for others, that can have a big impact on the overall relationship.

There are other, deeper cultural differences that have been identified through research, for example by Geert Hofstede and others building on his work. How many of us working in other societies would be able to comment on the differences in ‘power distance’? Or whether they are ‘low’- or ‘high-context’ communication environments?

There can also be big differences between institutional sectors: the public, private and not-for profit sector speak different ‘languages’ and often seem to operate according to a different logic. This can make it difficult to establish cross-sectoral partnerships. As the military got more involved in international humanitarian action and reconstruction, they and NGOs had to get used to very different institutional cultures. But there are also differences in institutional cultures between organisations in the same sector: e.g. among military contingents from different countries, as every Force Commander of a multilateral peacekeeping operation knows, and between NGOs. The ‘culture’ of MSF is not that of Worldvision.

When working in the Ogaden, I regularly found myself the mediating interface between Somalis with their ‘egalitarian’ social behaviour, and Ethiopian Highlanders with a hierarchical, deferential one. Effective advising also means learning to sense different societal and institutional cultures, and find a good fit, mostly working with the grain rather than against it.

Change processes. Technical-thematic experts are deployed to contribute to improved institutional performance. That usually requires ‘change’. But like most of us, few have a practical framework to understand and guide ‘change processes’. Only one phenomenon stands out: resistance from the other, typically the national colleagues. Foreign advisers are usually blind to the often profound ‘resistance’ to change in the international development partners, and possible ‘resistance’ in themselves. We rarely analyse the very different reasons that can underpin ‘resistance’. Perhaps the development partners have created ‘reform overload’: too much too fast? How many experts have a conscious repertoire of tactics to try and reduce / overcome resistance, and an understanding of how ‘change’ at a larger scale -and over a longer period of time- actually happens? One thing is certain: it will not be ‘according to plan’.

Different types of advice. Too many advisers still operate with the belief that they can or always must provide ‘solutions’. In some instances, this can be appropriate. There certainly will be the expectation and pressure, from both the home and host country, to do so. Is that not what ‘experts’ are for? And yet, in practice we then often end up imposing external models, that may not be the best fit for where the national institution is now, that are not owned and will not be sustained.

As I mentioned in an earlier blog (‘Complexity, contractors and consultants’) advisers can also provide the national counterparts with ‘options’ to choose from, or simply ideas to consider. Or recommend a process that brings into a collective reflection the range of key stakeholders and experts, to collectively work through the diagnosis and develop solutions that can get broad support and will be workable.

Sometimes this happens, taking the form of a somewhat larger ‘policy community’. Recommending a process that would involve the wider public, or citizenry, is exceedingly rare however, and would probably be considered quite ‘extravagant’. And yet, that is precisely how a healthier governance relationship, between people and authorities, can be created. In Guatemala, a number of Guatemalan civil society organisations were actively part of the policy community working through the challenges of security sector reform and democratic security though there was no broader public involvement. In Burundi, a key adviser to the security sector managed to mobilise some public engagement, to get the security personnel to understand how they are perceived and what the public expects from them.

If we don’t encourage public participation in institution-building and public policy development, then our international cooperation de facto encourages technocratic elite- rather than more participatory governance.

V. MANAGING DILEMMAS.

Expert advisers can also expect to be confronted with different moral and effectiveness dilemmas.

Some common effectiveness dilemmas:

Ø Rhythms and speed: The formal planning, budgeting and implementation schedules of international and national actors do not always align. But beyond ‘formal time’ there is also ‘political’ and ‘social’ or ‘anthropological’ time, which may have a critical influence on the actual effectiveness of the effort. Whose ‘time’ and ‘rhythms’ will the advisor follow? Does s/he ‘step in’ and ‘step up’ by becoming more ‘hands on’ in order to move things forward, or does s/he stay with the often slower rhythm of nationally-driven capacity-strengthening and institutional reform? When does this become acceptance of a problematic ‘status quo’?

Ø Local solutions – international standards: Does the advisor encourage and support ‘local solutions’ (that, for the time being, are the ‘best possible fit’) even if they fall quite short of what are held to be ’international standards’?

Ø The right to learn through trial – and sometimes error? Does the advisor ‘allow’ the national actors to ‘experiment’ and to ‘learn-by-doing’, including to ‘learn from mistakes’, even if s/he is very sceptical that their proposed move will produce results?

Ø What responsibility regarding sustainability? Does the advisor encourage the creation of internationally driven and –supported structures and procedures, even if it is clear that they will not, in the medium-term future, be sustainable with national resources and skills only?

Some possible moral dilemmas:

Ø Advisors may find themselves in situations where they have to work closely with people that are suspected or known to be responsible for serious human rights violations and to have ‘blood on their hands’. But who – for political purposes- have been co-opted in the current governance structure. Are they unwittingly complicit in perpetuating ‘impunity’?

Ø Advisors often find themselves in a situation where they have to answer to multiple bosses, or at least multiple stakeholders: minimally their national counterpart(s), their field- or mission-level superiors, and possibly their home government who mobilized them in the first place. International actors may ask them for insight information about what is being discussed and happening within the national entity they are working with. The latter may suspect them of ‘being spies’ for one or more international actors, and may even deliberately try to ‘test’ the advisors on this. Where do their loyalties lie, who do they see themselves as most accountable to?

Are you ready to be an expert-adviser in another country?

[i]Pioneering work to better prepare expert advisers was undertaken by Nadia Gerspacher of the US Institute for Peace. Together with Jan Ubels and Nora Refaeil, we built on this work and took it further in the development of a course on ‘Effective Advising’. For a more extensive discussion of these issues, see my papers ‘Value for Money?’ and ‘Jill and Jack of all Trades’.