“They just don’t understand what the realities are!” Have you heard such statement of exasperation from programme people about a potential or actual institutional donor? Not infrequently they are right: even in volatile situations and with objectives that require behavioural change from influential others, we are often asked to submit to the illusion of ‘control’ and present overly detailed plans, budgets and timelines.

Fortunately, there are also institutional donors that learn. That can be seen in the recent tender ‘Addressing Root Causes of Conflict and Irregular Migration’ (ARC) of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The ARC Fund was available for NGO applications and for 12 identified countries. Both in process and in content it represents a sophisticated approach.

1. The Process.

Some donor choices stand out as quite unusual or even innovative:

- By setting (with strong input from the embassies) country-specific priority objectives that also represent important milestones in the Ministry’s general ‘theory of change’ regarding ‘security and the rule of law’, the tender successfully reconciled country-relevance and policy-relevance;

- Applying NGOs were not asked to submit a detailed proposal and budget, but a Track Record and a Concept Note in line with detailed guidance. This in recognition of the fact that developing a detailed proposal requires much time investment, which may not result in winning a grant. And it leaves less scope for further discussion between donor and operational agency about specifics of the planned programming – which is meaningful if there is a stronger ‘partnership’ intent;

- The Track Record, already used in previous tenders, signalled a belief that addressing key drivers or root causes in a country (or specific priority region within), is unlikely to happen if the operational agency is not already well experienced there, and has no prior experience with programming around challenging objectives such as ‘more inclusive and responsive governance’ or generating ‘income-opportunities’ that can reduce the drive to migrate;

- Because the Ministry wants to promote less competition and more collaboration, its intent is towards ‘partnering’ rather than ‘sub-contracting’. This manifests itself in a readiness to provide thematic support on particular interest areas such as conflict-sensitivity, gender, partnerships and monitoring & evaluation. And in an invitation to grantees, to collaborate in the development of an overarching ‘results framework’ that will make it easier for the Ministry staff to report on the overall effectiveness of this Fund investment.

- No less significant is the fact that the grants are for 3-5 years, with the understanding from the donor that programmatic adaptations will likely be the norm rather than the exception within such time frames.

2. The Content.

The guidance for the Track Record and Concept Note submissions shows a donor administration that has been learning quite well, and wants to see similar learning reflected in the conceptualisation and design of the programmes it funds.

a. The Track Record had to consist of two case studies relevant to the specific objectives for the country that the applicant sought funding for. One of the case studies had to refer to the country itself, and at least one of them had to be supported by an internal or external mid-term review or evaluation.

Explicitly requested attention points in the Track Record were:

- Substantive involvement of local partners and of the target groups, that shows that the action is locally owned and there is local accountability;

- ‘Complementarity’ of the action with that of others working in the same environment or on similar issues – though allowing also for innovative programming;

- Not just ‘gender sensitivity’ but a conscious interest to support ‘gender transformation’, in situations where women do not enjoy equal rights;

- ‘Conflict sensitivity’ especially in the sense of awareness about the impacts of the programme and the agency on the overall dynamics of conflict or peacefulness in the operating environment;

- The quality of the monitoring and evaluation practices;

- The effectiveness of the past programming at the outcome level – with attention to whether the outcomes were formulated in a ‘SMART’ way;

- The provisional sustainability of the results achieved, accepting that there are multiple dimensions to ‘sustainability: organisational capacities; financing; something being institutionalised by law, social sustainability (i.e. interiorised behavioural changes) etc.

b. The Concept Note had to be built around four major themes:

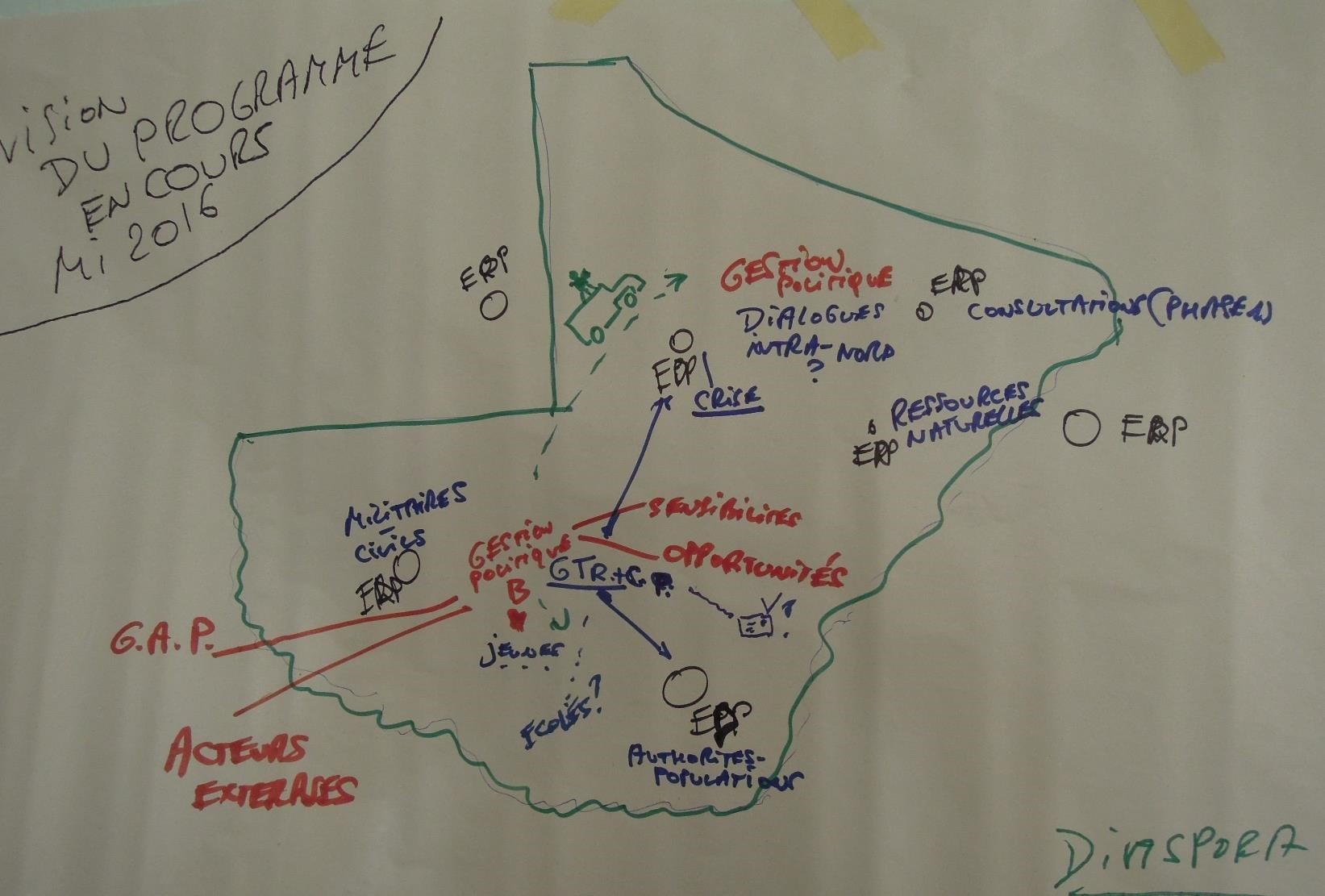

- Context & actor analysis: what are the drivers and contributing factors of conflict and irregular migration (from the local to national, regional and where applicable international levels); who are the relevant actors that are part of the problem or can help resolve it; the power dynamics among them; where do the applicants sit within the actor dynamics; what are the gender relations and gender power dynamics in the proposed programming environment. Those proposing to engage in activities to create more income opportunities had to provide a market analysis. All this analysis can result in a clear problem statement.

- The Theory of Change for the proposed programme, that creates a credible and plausible link between the problem-statement and the intended outcomes. Attention was required here to the strategies to achieve the outcomes, the assumptions underpinning them and whether the strategies are within the sphere of influence of the applicant. An argument also had to be provided regarding the complementarity of the proposed programme with the efforts of other actors, and the strategies envisaged to increase the chances that positive results can be sustained.

- Added value and relevance: Here the applicants that apply as a consortium were asked to explain what the added value is of working in a consortium (general), and what the added value is of their specific consortium. They can also make a pitch for why their proposed programme is strategically relevant for the identified priority objectives in that country.

- Conflict sensitivity: The applicants were expected to demonstrate that they can practice conflict sensitivity, and ensure their local partners, contractors etc. can as well. When the proposal concerns an economic activity, they were to demonstrate that they will responsibly manage the risk of market distortion.

The choice for a longer duration, the encouragement of collaborative work and a recognition that adaptations along the road will be almost inevitable, make this ARC Fund and tender a ‘progressive’ endeavour. In its content, it also integrates important ‘lessons identified’ (though not everywhere ‘learned’!): Attention is paid to the potential interconnectedness of ‘contexts’ at different levels, and to power dynamics among actors and between genders. Agencies are asked to reflect about their own position in the actor-landscape. Where they envisage economic activities, they need to go well beyond ‘vocational training’, and underpin their proposals with a credible market analysis that also looks at demand, the role of the private sector, financing facilities etc. The Dutch have opted to use the ‘theory of change’ approach which is potentially more sophisticated than the now mechanically used ‘logframe’. They rightly focus on the likely area of ‘influence’ of the applicants. Complementarity or added value is another explicit attention point, as are gender, conflict-sensitivity and strategies towards sustainability.

It could also have been appropriate to encourage the applicants to do some explicit ‘scenario thinking’ – not a luxury when considering a 3-5 year horizon in rather volatile environments. This can still be introduced at the subsequent stage of detailed proposal development. With regard to assumptions underlying the tender, questions can be asked whether better local income-opportunities will be sufficient to decrease the perceived necessity or desirability of migration. ‘Irregular’ migration tends to be driven by a variety of complex motives, and some have argued that better incomes actually allow prospective migrants to cover the costs of ‘irregular’ migration.

Overall however, this is a high quality tender, that integrates and promotes various important attention points that in discussions and trainings tend to be separated out. As such it promotes and supports sophisticated programming: Producing a credible ‘Track Record’ as requested here, requires not just effective M&E systems, but overall reflective practice and solid documentation. A ‘Concept Note’ of this calibre cannot be produced by a professional proposal writer without significant substantive input.

The other side of the coin is that the bar here gets very high for quite a number of NGOs. Even if an organisation or consortium/partnership of organisations has been doing very good and relevant programming in one of the target countries, not all of them have the quality of documentation to put together a strong written ‘Track Record’. While many aid workers have now heard about ‘theories of change’, for decades they have been forced to think ‘logframes’. Presumably many would be challenged to explain succinctly what the differences are between both and why a ‘theory of change’ approach might be superior? ‘Power analysis’ (or what is also referred to as ‘thinking and working politically’) is not part of the daily mind-set in a sector that has long pretended that the problems and their solutions are largely ‘technical’. Most aid-supported interventions related to conflict & peace still tend to work on a particular level (local, intermediary, national…) with no or limited cross-linking between levels.

We can certainly see how these requirements become even more daunting for many national and local organisations. Even if their work is as sophisticated as requested, they may stumble over the need to demonstrate this, in a limited number of pages, in English. Not many made a bid as lead applicant. If the ultimate aim of external support is to strengthen the local capacities for peace and equitable development, then this remains a strategic attention point. Not only to enable them to access aid money, but also to understand better where the sophistication in their ways of working may lie.