The siege tactics of the Syrian government and its allies are today’s most brutal illustration that national authorities (and their international allies), when party to the conflict, may indeed be unwilling to honour fundamental humanitarian principles.

That was less the case during the long war in Sri Lanka. There the government maintained a skeleton administration in LTTE controlled areas, and allowed a controlled amount of food, medicine, and other necessities to enter in what was otherwise a zone cordoned off by an internal sanctions regime. After we, an international relief and development agency, had rapidly scaled up our relief operation in response to the internal displacement of several hundred thousand people, the LTTE started insisting that we provide the items to Tamil NGOs in that area, rather than distribute ourselves. We already had some such local collaborators, but also realised that this was likely to be an attempt to gain indirect control over the relief items. Though we did involve some Tamil NGOs, as well as several governmental ‘District Agents’, in the operation, we largely continued to run it ourselves. Not because we had evidence to doubt the integrity of our Tamil NGO colleagues, but because we knew that the LTTE could exercise pressure on them, that would be hard to resist.

In a very different setting, in what is now the Somali Region 5 of Ethiopia, my Somali colleagues and Ialso often prepared our ‘roles’ before engaging on challenging issues with other Somali actors. They would manage most of it, but I, as foreigner outside the clan-system, would come forward to deliver the more difficult messages that ‘no, sorry, but it is really not possible to…’. Even if my Somali colleagues fully supported our organisational position, an outsider delivering the tougher messages reduced the risk of them being accused of clan-bias and coming under direct or indirect pressure.

So there is indeed some validity to the cautionary tone about ‘localisation’ in conflict.

II. Pride and Prejudice?

Where the argument gets problematic and disturbing, is in the assumption that international agencies are generally and intrinsically much better at operating with neutrality, impartiality and independence. This ‘holier than thou’ tone smacks too much of pride and prejudice. Why?

1. International agencies can take sides.

Certainly during the Cold War period, many international agencies provided financial, practical and moral support on the basis of ‘solidarity’ with one side or another. This was the case in Central America, in support of the ‘mujahedeen’ in Afghanistan until the fall of the Najibullah regime, in the armed struggles against the Mengistu regime in Ethiopia, and in the long war of then ‘southern’ Sudan against a regime in Khartoum seen as discriminatory and repressive.

2. Many relief agencies are not financially independent.

While some, such as the ICRC or MSF have great diversity of funding or raise significant funds directly from the public, many others fund their relief operations through bilateral or multilateral grants. At least part of this funding comes through bidding in response to a ‘call for proposals’, that has been shaped by the donor.

Grants from multilateral agencies such as the UN or the EU, may be less vulnerable to being associated with a political agenda than those directly from individual donor governments. But most official funding remains susceptible to media attention and political interest. So many relief agencies have to follow the money; fairly often that money reflects the agendas and priorities of the donor government, or can be perceived and portrayed as such. ‘Visibility’ requirements imposed by the donors, such as their logos on vehicles used in the relief operation, or on food bags, result from an understandable logic. But they clearly associate the relief provider with certain bilateral or multilateral actors.

3. Relief agencies do not operate in a vacuum.

Anyone spending some time in Gaziantep, the southern Turkish city which has a concentration of agencies that support work in northern Syria, realises that this is not just a ‘rear base’ for humanitarian action. Other actors with military, intelligence and political interests and objectives, also operate out of Gaziantep, as they did in the late 80s out of Peshawar and Quetta. While I do not believe that relief operations habitually serve as cover for other activities, we cannot assume that there are perfect firewalls that prevent any contact, even unintentional. Minimally, information about relief work is relevant for actors with other interests.

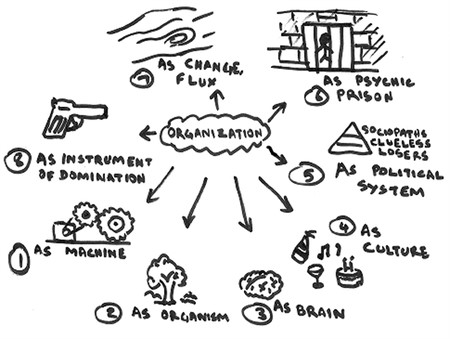

4. Most aid agencies are multi-mandate.

The great majority of agencies, UN, NGO or CBO alike, are ‘multi-mandate’. They don’t do just ‘humanitarian’ work. They are involved in social and economic development, conflict reduction and peacebuilding, human rights, women’s rights, good governance promotion etc. When faced with a major crisis, they also carry out relief work, which may very well be in accordance with humanitarian principles. However, as a Taliban militant pointed out the staff of an agency that had been working in Afghanistan for a long time: “Before, you were providing basic medical care to our children, and that was fine. But now you want to change our women and their place in our society. That is not acceptable.” The same agency had gone from medical relief to social transformation. This Taliban militant did not see two different agencies, but one and the same.

The ‘humanitarian sector’ projects an image of itself that partially plays linguistic tricks and relies on mental compartmentalisation: Many are involved in ‘relief’ (which may be very justified and do a lot of good), but not all of that is always fully ‘humanitarian’ i.e. in strict adherence to ‘humanitarian principles’. And doing ‘humanitarian work’ in certain situations, doesn’t make a full-time ‘humanitarian agency’. Our Taliban observer saw it differently. He is not the only one.

5. There is no magical transformation of relief workers.

Those who question the ability of nationals, in general, to be neutral, impartial and independent in conflict situations also believe in magic. Or would like us to do so. Because it suffices then for that national to be hired by an international agency, to undergo a magical transformation, or ‘rebirth’ into a fully-fledged ‘humanitarian worker’. Indeed, the same person who, when working with a local organisation, might be the object of doubt, has a good chance of becoming a trustworthy individual by changing employer. Not only that: they are now suddenly capable of providing the necessary oversight whether the local organisation is indeed adhering to fundamental principles.

Outsiders, ‘international’ aid workers with no connection whatsoever to the environment where the conflict rages, are also not suddenly individuals without opinions. Most of us are vulnerable to the ‘good guys-bad guys’ syndrome. The good guys may be the ‘government’ and the bad guys the ‘terrorists’; or we sympathise with the ‘underdog’ fighting a repressive regime, or with a wider population long-suffering from a corrupt or authoritarian government etc. Or we like the ‘peace camp’ but not the hard-line ‘nationalists’. We may try to work on all sides or provide relief ‘impartially’. But few of us have the sustained self-discipline to ensure that our personal readings and judgments about the situation never show in our behaviour and are never overheard.

III. The Dynamics of Security and War Economies.

The ability to abide by humanitarian principles is not only dependent on an aid agency’s intentional positioning. It is inevitably also dependent on the humanitarian space allowed by the armed groups. If an armed group, like Al Shabaab for example, does not allow aid agencies to operate (independently) in the territory it controls, or threatens the life and security of its staff, its ability to act with full neutrality and impartiality will de facto be limited.

That ability may also be affected by the nature of the goods and services provided: clothes, hygiene kits and immunisations have less value in a war economy than, say, medicines, food and construction materials. Armed groups are more likely to try and interfere, directly or indirectly, with the provision of the latter.

Surprisingly, relief-providing agencies, over the past 20 years have invested a lot in the practical competencies to systematically analyse and manage security risks. But very little, by comparison, in understanding war economies and how aid can be drawn into them. No wonder then that integrating ‘conflict sensitivity’ into programming still remains a major challenge.

IV. Independent Assessment and Verification: Internationals Only?

Hofman and Heller Pérache have shared a fascinating reflection about MSF’s thinking about ‘direct action’ and ‘remote management’ in Somalia, Afghanistan and Syria. [i] The discovery that the provincial hospital in Lashkar Gah was not operating as per its reports to the Ministry of Health in Kabul, but largely provided the supplies for its staff to run their various private practices, is a powerful example of what can happen when there is no ‘independent’ oversight. The alleged ‘passivity’ of Somali MSF staff in other project areas, to the impact of the 2011 drought in Al Shabaab controlled areas of Somalia, even if they too were not allowed access there, is another example invoked that raises the question whether the fundamental integrity of the organisation can be maintained, when only local & national staff are in the field?

Such examples are not to be brushed aside. But they need to be balanced against the reality that MSF has occasionally completely pulled out of conflict areas because some of its staff were assassinated, thereby stopping all its medical humanitarian services. My own experience with Somali and Afghan, and other ‘national’ colleagues in many countries, does not confirm the impression left that – ultimately- all local and national staff will compromise too much on principles, be it intentionally or under pressure. Indeed, it have always been -dedicated and trustworthy- national colleagues who provided me with the necessary insights and guidance that allowed us to maintain humanitarian principles and thwart the sometimes very subtle attempts at manipulation by armed or otherwise influential actors. Nor have I seen widespread political skills among international staff, to negotiate and maintain a ‘neutral’ and ‘impartial’ positioning in complex and dynamic environments with a multitude of actors.

V. What About ‘Humanity’?

Conversations about ‘humanitarian principles’ tend to focus on the trio of neutrality, impartiality and independence. Rather conspicuous for its absence is the first one of ‘humanity’. Presumably it is assumed that anyone involved in relieving the distress of others, cannot but experience our shared humanity as a driving motivation.

Observation of relief work in action confirms that there are many individuals indeed who show strong compassion. But also that for too many others this simply seems to have become a job and even a ‘career’ like any other. Arrogance, indifference, disrespect, unwillingness to listen, sometimes even racist behaviour, are not, in practice, adequately prevented and challenged by agency’s ‘codes of conduct’.

The whole ‘professionalisation’ of ‘humanitarian’ action can also easily lead to ‘dehumanisation’ of crisis-affected populations. The language of the relief world already contributes to this: People in New Orleans affected by a hurricane, Germans and Brits affected by flooding, or Italians from villages damaged by earthquakes, by and large remain citizens of their countries, with an individual and social identity. But people affected by crises in other continents quickly lose identity. They become ‘IDPs’ or ‘refugees’, ‘needy people’, ‘beneficiaries’… labels that allow them to receive free relief goods and services, in exchange for a significant reduction in identity, dignity and autonomous ability to act.

The anonymisation of individuals and groups can continue well into the ‘stage’ of recovery and rehabilitation. I remember vividly driving around in Liberia some years ago, in the mysterious terrain of ‘signpost land’. At the entrance to every village and hamlet was a signpost summarising the project being implemented there and the responsible agency. Absent however were the names of the location: the identity of the locality was obviously assumed to be of far less interest to the traveller than its being the site for an aid project.

VI. A Deeper Humanity? Shared Wounds, Resisting Fragmentation.

Luz Saavedra’s ‘listening research’ with Lebanese and Colombian non-governmental organisations, reveals that many of them act according to deeper motivations than just providing ‘relief’ in time of need.[ii] They also see themselves as social and political actors that are part of a shared society. They are very conscious of the deeper wounds and damage that indifferent governments and violent actors, of all kind, inflict on the natural ‘affective solidarity’ between people and within most communities. Their assistance and presence seeks to go beyond ‘saving lives and alleviating suffering’: it is also an act of resistance against these forces of fragmentation, and of positive affirmation of a belief in a healthier future society. For them, humanitarian action is not just a parcel delivery service but also a relationship. Which is, as the ‘Listening Project’ of CDA Inc. has told us clearly, also what people around the world value and expect.

They often keenly observe how the international humanitarian machinery, through its internal competition and its heavy footprint, contributes to that fragmentation, disempowerment and dependency of people. With and on behalf of people whose autonomy has already been heavily reduced, they may challenge the authority of international actors where their modus operandi contributes to the same.

In short: Maintaining humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence in conflict situations is very hard – for national and international actors alike. With very few exceptions, most agencies cannot claim to be intrinsically excellent in this. International agencies and actors tend to overstate their own track record and abilities in this regard, and to downgrade that of national and local actors. That reflects prejudice more than evidence. Every situation will require its own, ongoing, assessment. There are certainly situations where ‘outsiders’ can play a role that is harder for to play for ‘local’ actors. But the next day can bring a situation where the reverse holds true.

[i] M Hofman & A Heller Pérache 2014: From Remote Control to Remote Management, and Onwards to Remote Encouragement? The evolution of MSF’s operational models in Somalia and Afghanistan. In International Review of the Red Cross. Vol.98: 1177-1191

[ii] L. Saavedra 2016: “We Know our Wounds. National and local organisations involved in humanitarian response in Lebanon” & 2016: “Learning from Exposure: How decades of disaster and armed conflict have shaped Colombian NGOs.” London, ODI/ALNAP